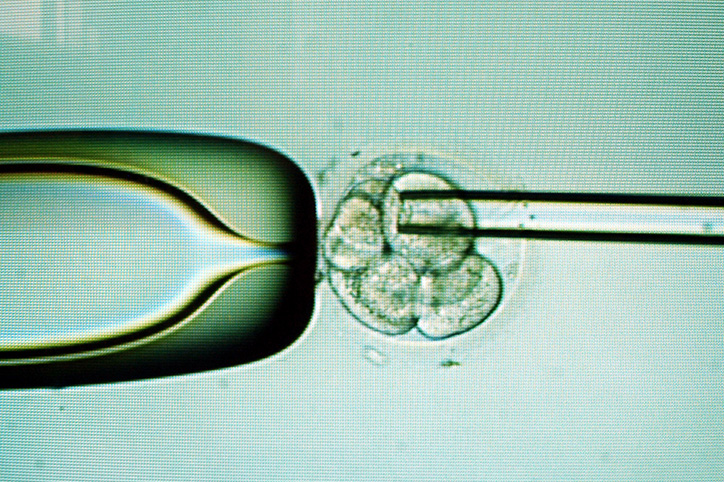

Anyone who has done in vitro fertilization (IVF) is familiar with preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) and the dilemma involved with it. When a woman does an IVF cycle mature eggs are collected from her ovaries (after about 10 days of hormone shots) and fertilized by sperm in a lab. Then the fertilized embryo (or embryos) are transferred to the woman’s uterus. Some women opt for the additional step of PGT. This means that instead of doing a transfer after monitoring the embryo(s) 3, 5 or 6 days in a lab, a small number of cells are biopsied from the embryo(s) on day 5 or 6 and sent for testing. Embryologists look for possible genetic problems that can cause implantation failure, miscarriage and/or birth defects in a resulting child. The idea is that PGT testing will show which embryos have the best chance for viability.

Sounds like a no-brainer to do PGT, right? Not so fast.

First off there are three kinds of PGT.

- Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): A healthy embryo should have 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell. Unfortunately, it’s very common for embryos to have chromosome abnormalities wherein there is a missing or an extra chromosome (aneuploidy). These embryos often end in miscarriage or a failed IVF cycle though they sometimes also lead to a live birth of a baby with a chromosome condition such as Down syndrome.

- Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M): This testing is done when one of the patients involved has an increased risk for a specific genetic condition that could be passed on to the baby.

- Preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR): This type of PGT is performed when one of the parties involved has a rearrangement of their own chromosomes, which puts them at an increased risk of producing an embryo with missing or extra pieces of chromosomes.

If you are concerned about a specific issue there is less of a dilemma. In fact, many women opt for IVF specifically for PGT if they know, for example, that they carry the BRCA gene. For women looking to do PGT-A, however, the question isn’t so clear cut.

For one, PGT is an expensive testing process. Then again, so is the transfer of an embryo. These two costs need to be weighed against one another and they differ from clinic to clinic and based on the individual insurance plans. The number of embryos that a woman has at her disposal to transfer also varies widely. There have been a number of stories of women who transferred embryos that weren’t considered to be likely to produce healthy children and went on to deliver healthy babies, which is why a woman who was only able to produce a single embryo after her IVF cycle may not want to do PGT. She may take her chances and transfer her only shot at a baby, especially since there is a small chance of damaging the embryo in the PGT process. By contract, a woman who produces a dozen embryos may want to do PGT to test which embryo has the best chance for success from her many options.

While recommendations differ greatly from doctor to doctor and case by case, often PGT-A is only considered for patients who have had recurrent miscarriages, multiple failed IVF cycles, a prior pregnancy with chromosome abnormalities or when the woman is of “advanced maternal age” as the older a woman gets, the less likely her eggs are to be viable. Aside from cost, as mentioned, PGT testing isn’t foolproof. The cells that are biopsied come from a part of the embryo that will eventually form the placenta. The idea is that these cells represent the rest of the embryo, but while that is often the case, it isn’t always the case.

Bottom line: there are many factors that come into play when deciding whether or not to do PGT, so it’s always best to speak with a doctor you trust about your specific case.